When we lived on kibbutz, I held a number of jobs. I worked in the refet, the olive & pickle factory and I held a number of jobs in the chadar ochel. One other job that I had part time was teaching English to the children of native English speakers in the elementary school. Although I’d taught in the past, I never studied education, so my classes were always somewhat … experimental (read “improvised”.) We’d mostly play games, often discussing popular culture (one of the students, I think in 5th grade, was the child of Israelis, but had learned all his English watching The Simpsons. He actually had the highest level English in the class.)

Anyway, this Shabbat I saw one of the kids who I taught, and it reminded me of a story about him. I was trying to teach some of the younger kids (second and third grades.) This kid felt that being with the younger kids was a bit babyish, and was trying to “play it cool.” He wasn’t interested in any of the games that I suggested. I asked him what he liked to play, and he said soccer. So I invented some kind of game on the blackboard, where if a kid would name an animal in English, he could score a goal. He was into it, while still attempting to remain cool.

When it was his term, this cool kid, came up with the following animals - “horsey, doggie, piggy…” I had a hard time not laughing!

That certainly made me think about the risks of talking in “baby-talk” to our children.

But I guess I got my comeuppance for my attitude a couple of months ago.

I work in an area of Jerusalem where the mounted police patrol regularly. They also use our parking lot as a place to park their horses when they want to come in for lunch.

One day when I was leaving work with an English-speaking friend from my neighborhood, I noticed that one of the mounted policemen leaving the parking lot was also from our town. I innocently said, “Hey, look! There’s Dudu” (the cop’s name, a common Israeli nickname for David). However, my friend: a) didn’t know the cop, and b) noticed one of the natural functions that the horse was performing at the time, and therefore replied to me “Well, that’s what horses do!”

I was pretty embarrassed. Not only did it seem that I had some bizarre need to point out the horse’s defecatory behavior, but I sounded like a four year old saying it!

Monday, October 31, 2005

out of the mouths of babes

Sunday, October 30, 2005

ASL Browser

I grew up in Rochester, one of the two cities in America (at least then) that had a univeristy for the deaf (NTID in Rochester, Gallaudet in Washington.) There was a lot of exposure to the deaf and to sign language. Most kids - I think - at least knew how to finger-spell. I also tried picking up a number of signs, most of which I've long forgotten.

It was a pleasure to come across this site, which has Quicktime video for the signs of hundreds of words:

ASL Browser

Thursday, October 27, 2005

recent reading

I haven’t written a post about my reading habits in a while. So the larger number of listings is due to the time between the posts, not because of a quicker clip on my part.

First of all, I finished the latest Harry Potter. I saw a really funny idea about what might be the end of the next book. To see it – click here. (But only if you’ve finished #6).

I also read two great books by Malcolm Gladwell – The Tipping Point and Blink. While those books were later recommended to me, I was first introduced to Gladwell by a friend, who had me read an article of his on a topic that didn’t seem terribly interesting – ketchup. It turned out to be an amazingly interesting article. He has great insights into the way the human mind and human society work. I’m trying to figure out how to use his understandings to help me better comprehend Judaism. That will probably come later.

I’ve finished reading one of the first autobiographies I’ve read in years – Natan Sharansky’s Fear No Evil. After finishing it, I’ve gone back to reading Abba Eban’s autobiography. Both books are a great way to understand important chapters in Jewish history that I knew about, but not nearly enough. But two things surprised me in particular: a) both Sharansky and Eban have a great sense of humor, and b) they both accomplished so much at a young age. Not much older than I am. I can’t help but wonder what that says about what I’ve accomplished so far.

My mishnayot learning is going along, albeit a bit slower than in the past. I’ve finished Masechet Shabbat, and am now trudging through Masechet Eruvin. It’s actually more interesting than I anticipated, but it’s still difficult. At this rate I’ll be lucky to get to Pesachim by Pesach…

Wednesday, October 26, 2005

my opinion ... for a song

Well, Simchat Torah is behind us now. I enjoyed it, but I don’t remember ever being so tired. I think the combination of the long day - we started at 7:30 and finished after 13:00 - and the fact that my kids are getting bigger but still want to go on my shoulders for the dancing, is what’s doing me in.

I see that I’m getting older not only by the weight of my kids, but also by the songs. There are more and more songs every year that I simply don’t recognize.

But even from the ones I do recognize, there are some of questionable appropriateness.

Here are some that I’ve thought of:

- There is the famous story by the Maggid of Duvno that it is in appropriate to sing the last line of Avinu Malkeinu. But that is actually the line most likely to be sung.

- I remember reading in Rabbi Hershel Schachter follow up to Nefesh HaRav, "MiPeneni Harav", that Rav Soloveitchik was opposed to saying "Ana Avda D'Kudisha B'rich Hu" (I am a servant of God) in the prayer B'rich Shme, since it was haughty. I think the original quote was from the Chafetz Chaim, but I'm not sure. In any case, it's another popular song.

- My Rosh Yeshiva, Rav David Bigman was opposed to the popular (Chabad?) song Mashiach, Mashiach, since it put too much emphasis on (a) man, and not enough on God.

- Here's one that I've come up with myself: The famous song "V'Samachta B'Chagecha... V'Hayita Ach Sameach" isn't correct. The origin is from Devarim 16:14-15, and there are a lot of conditions between the first part and the last. They include adding others (the poor, widow, leviim, etc) to your joy and having it in Yerushalayim. Rav Hirsh in his commentary there says that without fulfilling those conditions, you can't achieve "v'hayita ach sameach."

Tuesday, October 25, 2005

Technorati's State of the Blogosphere

Technorati has an interesting post on the State of the Blogosphere.

Monday, October 24, 2005

What is this blogging thing?

I’ve managed to past my 100th post without noticing. I’m sure all of my myriads of readers were out having huge centipost parties, but by me it was quietly ignored…

Anyway, it’s time for some reflection.

I’m still not entirely sure of the purpose of this blog.

What is it like?

Singing in the shower?

Giving a speech in a public square?

Talking to myself out loud on a bus?

Leaving a diary unlocked in the living room?

Graffiti on a wall?

A letter to the editor?

Anyway, I’m not sure. And that makes it hard for me to determine what I’m writing, particularly since I don’t know who I’m writing to. Do I care who hears what I’m saying and why?

I think that one of the main reasons for the lack of clarity as to my intended audience is that I haven’t made it clear who I am.

From what I’ve seen, there are three kinds of bloggers.

There are those that clearly state their name. Two of them that I read regularly are David Bogner’s Treppenwitz and Dr. Jeffrey Woolf’s My Obiter Dicta.

On the other side of the spectrum there are those who give no clues as to their identity. I’m not a regular reader of these, but there are plenty. Usually they’re written by individuals who want to write about something rather private, and can’t afford to reveal their names and still write openly.

And in the middle, are those who don’t mention their names directly, but if you read between the lines it may be possible to figure it out. In this group I would include Chayyei Sarah and Ben Chorin.

Some bloggers from the first category have claimed that it is more ethical to put your name on what you write. No hiding behind a mask. Additionally, it’s much easier to promote your blog if you don’t have to hide your name.

I’m not sure I agree with the first point. I think a decent metaphor for a blog could be Spiderman’s costume. (Superman’s costume really doesn’t count for something like this. Without a mask, it’s basically pajamas.)

On the one hand, you’ve got Tobey Maguire. He wears the costume, but wants everyone to know that it’s him. He demands (I assume) that his name appears in the credits and on the posters. He’s not interested in any sense of anonymity.

On the other side you’ve got Peter Parker. He doesn’t want anyone to know that he’s Spiderman. He wears the costume in order to protect his secret. If everyone knew who he was, he wouldn’t be able to function.

And what’s the middle ground? If I (or more likely my son) was to wear a Spiderman costume to a masquerade party, I wouldn’t be devastated if someone were to guess my secret identity. In fact, at some point I’d probably like it. But I’d like people to first try to guess if it was me – would I be the kind of person to wear that costume? Do I fit the role? And if I made the costume myself – how does it look?

And I think that’s what a semi-anonymous blog is about. I don’t have any deep dark secrets (at least that I’m writing about here.) And I’m sure with a minimal amount of detective work, a reader could figure out who I am. That wouldn’t bother me. I’d actually be honored that somebody cared enough to try.

So I think for now I’ll stick with it as it is. For those of you who come by here at times, I hope that my words speak for me. However, to know whether this is really singing in the shower or a public address, it would be nice to know who you are…

Wednesday, October 19, 2005

Basic Chemistry

I made a comment to someone today about how I am opposed to break-away minyanim. I added that not only break away minyanim, but breaking away in general – in family, in shuls or in national politics.

On the other hand, my approach that says compromise and avoidance of machloket has the status of l’chatchila is often viewed as wishy-washy. If I really believe in something, why should I compromise? Maybe the other side should be the one to avoid machloket?

At my son’s brit, I said the following:If “mila” (circumcision) is important, why isn’t a child born circumcised?

Mila is part of a brit, a covenant. There are many kinds of britot, such as treaties between nations, and even marriage (a brit nisuin). A brit can only exist when both sides are not whole, and are lacking something. We learn this from nature: Inert elements, like helium, cannot combine to form molecules. Only elements that are missing electrons or protons can combine to from a new molecule, as hydrogen and oxygen combine to form water.

There are those who object to circumcision because they claim that a child is born perfect. Judaism rejects this, for a child is born cute, but not perfect – either physically or ethically. We have a religion of mitzvot, of taking action. What mitzvot can a baby keep? What chesed can he do? Other than smiles, he can only receive, not give.

I notice from my work in the refet that calves can walk and do almost everything adult cows can do right after birth. Humans, however, need to develop first. For a long time this question bothered me: Why should it take humans so many years to mature? The answer we see is that humans have a higher ethical level to achieve than other animals. Therefore, their physical development runs parallel to the ethical development.

Mila is a physical sign of our acknowledgement of his lack of perfection, of his need to develop. Once we admit to this deficiency, we can make a brit with our Creator.

This is critical to understanding why I am opposed to “break-away”. A hydrogen atom does not want to break-away – when it is alone, it is incomplete. It is important we feel the same way when we are not connected with other members of our family, our community or our nation. I never want to feel so “inert” that I can be completely independent of the “other”.

There is another aspect of this that I’ve developed over the years. Of all the punishments available to the descendants of Moav, why did God insist that we don’t marry them? I think the reason is that they did not show willingness to allow Bnei Yisrael to cross through their land. They followed the principle of “sheli sheli v’shelcha shelcha”, i.e. midat sdom. And davka the descendants of Lot should have realized that the approach of Sdom was wrong, and that of Avraham was correct. But again, why the prohibition on marriage? Because in a marriage, you can’t have “sheli sheli”. The basic concept of a marital union – a brit – means that both sides concede to each other. It would be impossible to marry into a nation that has “sheli sheli” as an ideology, not as a punishment, but simply because marriage isn’t a logical option. (Perhaps that is why Rut was able to successfully marry into the Jewish people, because she so obviously rejected the concept of “sheli sheli”.)

And I feel that in almost any argument basic humility requires that I don’t claim to be 100% right. Certainly I’m convinced that my cause is just, but I have to leave a little bit of room for the other side to continue to exist. That’s the concept of “machloket l’shem shamayim”. Even though we follow Hillel, we still learn Shamai’s teachings. We don’t want them to cease to exist. Elu V’Elu Divrei Elokim Chaim!

Perhaps I’m naïve to believe that these rules from the beit midrash should apply in politics (family or shul, local or national), but these are my values.

Tuesday, October 18, 2005

yes, my sukkot post

Sukkot isn’t the easiest holiday for me.

I’ve known this for a long time, but this year, after my discussions about tradition, I’ve begun to understand my reasons a bit better.

First of all, I don’t enjoy it so much. I’ve found a quote from the Rambam to back me up on this:“Both these festivals, I mean Sukkot and Pesach, inculcate both an opinion and a moral quality. In the case of Pesach, the opinion consists in the commemoration of the miracles of Egypt and in the perpetuation of their memory throughout the periods of time. In the case of Sukkot, the opinion consists in the perpetuation of the memory of the miracles of the desert throughout the periods of time. As for the moral quality, it consists in man's always remembering the days of stress in the days of prosperity, so that his gratitude to God should become great and so that he should achieve humility and submission. Accordingly unleavened bread and bitter herbs must be eaten on Pesach in commemoration of what happened to us. Similarly one must leave the house [during Sukkot] and dwell in tabernacles, as is done by the wretched inhabitants of deserts and wastelands, in order that the fact be commemorated that such was our state in ancient times: That I made the Children of Israel dwell in tabernacles, and so on". (Moreh Nevuchim III:43, Pines translation).

In other words, the Rambam basically says that sitting in the sukka is comparable to eating maror on Pesach – by remembering the bad times, we appreciate what we have now.

But I think there’s more to it than that. Many people enjoy sitting in the sukka. Why don’t I enjoy the holiday?

I think it goes back to my lack of tradition. Growing up in a non-Orthodox home, Pesach and Chanuka had great significance, even if we didn’t follow the halacha. We went to “Temple” on Rosh HaShana and Yom Kippur. But despite going to Hebrew school, I have very little memory about Sukkot. We certainly didn’t celebrate it at home.

As I became religious in high school, I somehow managed to celebrate the holiday. I didn’t build a sukka, but for at least one year I purchased a lulav and etrog. But the time where I should have really learned what to do on Sukkot – during my 3 years in yeshiva in Israel – Sukkot fell during “bein hazmanim”. So I never got to watch my rabbis practice the customs and laws.

I guess on Sukkot, more than any other time during the year, I feel like an outsider, like a new baal teshuva. And while on other occasions I would simply study the laws to feel more competent, here I feel like there’s simply way too much to learn, and my natural difficulties in learning certain subject matters will prevent me from succeeding. In some ways I feel the same about tying tzitzit or the exact way to wear tefillin, but I’ve managed to at least feel comfortable in my routine, even if I’m not doing things perfectly.

So what do I do? I don’t want to take on every possible chumra, a) because that would be very difficult, and b) it doesn’t fit in with my general approach to halacha. So I get nervous. I try as much to rely on others to put up the sukka, to pick out the arba minim. And I feel jealous of those people who know how to bind and hold and shake their lulav because they simply do what their father did!

I’ve often said that I prefer Pesach to Sukkot because you need to prepare extensively for Pesach, but once it comes, you’re done. You don’t need to decide if this is or isn’t chametz. But sukkot you’re constantly (or at least I am constantly) wondering if the sukka is kosher or not, where in the world I’m going to find fresh aravot, etc. I think in my approach to dealing with lack of tradition, I’m more comfortable with “shev v’al taaseh” than I am with “kum aseh”.

I’m not sure what will improve the situation. I guess learning more about the halachot, but that is about as inviting to me as going back to the Cub Scouts and trying to learn how to tie knots. I mostly feel badly for my kids, since they’re much more likely to inherit their father’s neurosis about the holiday than any comforting traditions.

And if I’m already on a Sukkot rant, two other things:

- Since I usually work on Chol HaMoed, and my work has no sukka, I end up feeling like Sukkot is like Pesach. I have to constantly look for non-mezonot food!

- I don’t like wasps.

Sunday, October 16, 2005

My traditions

After reading my recent posts, you might think I don’t care about tradition.

Nothing could be further from the truth. I grew up in the home of divorced parents, not in the same town as my grandparents. I always wanted a more complete family life. Even as a young kid, I made a “Relatives Book” where every family member needed to fill out a page writing down all of their details.

Additionally, my father’s father died when my father was 4. And my paternal great-grandfather died when my grandfather was 7. There are major gaps in my family traditions (another post will probably describe how I found out we are actually Levi’im, not Kohanim).

My sometimes hobby/ sometimes obsession of genealogy - over 4000 names on the family tree and counting - I believe stems from an effort to connect to the generations past. And my calling up constant distant cousins and saying “You don’t know me, but we’re related” is a way to connect the past back to the present again. Tradition!

Now I have a lot of names, but no “traditions”. I can imagine that if I had my great-grandfather’s kiddush cup or melody for “Shalom Aleichem” - I would use them without exception. And if there was a food back in Skaudvile that my great-great-grandfather never ate on Pesach, I would gladly resist from eating it as well.

So am I a hypocrite? Maybe, but not because of this. First of all, tradition is important, but it doesn’t trump halacha, certainly for humra. I actually do have a memory of a kid having found my grandfather’s tefillin, but my rabbis said they weren’t kosher. I wish I knew what happened to them since, but I wouldn’t wear them despite the rabbis’ ruling. (I would however have no problem trying to find halachic justification for a potentially problematic tradition.)

But just like tradition doesn’t trump halacha, it also doesn’t trump all values. For, in the end, it is a value in itself. But other values also are important - humility, respect for others, etc. Why should my tradition take precedence over another’s tradition? Or another’s need for religious fulfillment?

Even now, I have certain family traditions that I cherish. They aren’t generations old, but in my nuclear family we have songs that we sing, foods that we eat, etc. But when I go to someone else’s home, I wouldn’t dare insist that they enable me to practice those customs. It’s not my house! It would be chutzpa to even bring it up.

The same applies on a community level. Everyone has the right to their own traditions, but has no right to trample the halacha, traditions or values of others.

what's in a name?

Over Shabbat, a guest got an aliya in shul, and I'm nearly certain he was called up as:

Ploni ben Chayim Ploni

If I heard correctly, that sounds like a very sad story...

Saturday, October 15, 2005

the best politicians are the ones not elected

Here's an email I wrote before the 2003 elections. Elections aren't that far away, and this message is very important to keep in mind.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I think people have a tendency to idolize prepoliticians. In this sense there is no real difference between Ehud Barak, Amnon Lipkin Shahak, Shaul Mofaz and Moshe Feiglin.

For example, look at the two leaders of Zo Artzeinu from the mid-90s: Moshe Feiglin and Rav Benny Elon. Both were strong ideologues - and I'm sure if you asked anyone then which one was likely to change the country, Elon would have been the more likely candidate.

Elon was elected to the Knesset, and while in opposition was still able to seem like a strong ideologue. Then his party joined the government, but he was still an MK, allowed to say what he wanted. After he became a minister, people accused him of selling out, of sitting with Labor, especially when it seemed like he was using political tricks to keep his seat.

Similar things can be said about other politicians - Rechavam Zeevi z"l, Effie Eitam, Avigdor Lieberman, Netanyahu, etc. All were popular in the "right wing camp" before they were elected, but berated by the pure ideologues after they entered the government and sat at the cabinet table.

While some of this can be attributed to the idea that power corrupts, or only corrupt people are attracted to politics, I don't think this is always such a negative concept. As the Prime Minister says, "What you see from here you don't see from there." Or as R.A. Butler said, "Politics is the art of the possible." Matzui over Ratzui, and so on. Ideals are important as goals, but they can't be the litmus test of a politician, because people want conflicting things, and it is up to the politician to sort them out. For example, if they had national referendums on whether public funding should be increased on education, on whether taxes should be reduced, and whether the deficit should be cut, all would likely pass. It is up to the politicians to decide how to balance conflicting desires. This is true in a quiet country - all the more so in a country like Israel, where every side feels that the fate of the country hangs in the balance. Israeli politicians have to make difficult decisions that we, the public, don't really need to make.

If Benny Elon sat with Shimon Peres, it is not because he sold out. It is because he had to weigh the importance of national unity against the importance of allowing some of the Left's ideas to be heard and even implemented.

Here's my prediction. If Moshe Feiglin makes it into the Knesset (I'm not sure that will happen), he'll already compromise a bit. He'll want to be on committees, etc, so he'll bend a bit. If he ever makes it to a ministerial position, he won't be the pure idealist that many of you view him as now. And that won't be a bad thing. He'll be a politician - the exact thing every person running for election is. Don't be surprised or disappointed.

The 20 Funniest People (I can think of right now)

The 20 Funniest People (I can think of right now):

Andrew Marlatt

Brian Regan

Conan O'Brien

David Letterman

Gary Larson

George Carlin

Stephan Pastis

Groucho Marx

Jerry Seinfeld

Jim Henson

Jon Stewart

Lore Sjoberg

Matt Groening

Mitch Hedberg

Norm MacDonald

Robin Williams

Scott Adams

Steve Martin

Steven Wright

William Goldman

Thursday, October 13, 2005

Einstein's socks

This might be getting repetitive, but I think I’m going to put up a few more thoughts about the halacha/mesoret issue.

- While both halacha and mesoret play an important role in our religious life, there is another important actor – values. Judaism is full of values like emet, shalom, hesed, kedusha, din, tzedek and more. Often both halacha and mesoret lead us to fulfillment of those values. But what happens when religious society ignores a value? Who can fix the situation? Mesoret is unlikely to help. While very powerful, it mostly uses the vehicle of inertia. Halacha on the other hand can be used to revolutionize. Sometimes to redeem an ignored value the halacha will make additional stringencies. Sometimes it will pull back, “uprooting” a particular practice for a more important value. The examples of this are endless. The prophets rallied against exclusive focus on sacrifices and ignoring social ills. The rabbis changed laws relating to shmitta, marriage, and others. Rabbi Eliezer Berkowitz documents this well in “Not in Heaven”. Of course the halacha is not to be toyed with lightly, but when circumstance warrants it – it does not roll over and play dead.

- There are two types of halachic approaches, which in many ways are opposed to one another. One is the approach described in Rav Solveitchik’s Halakhic Man. He describes a halacha that is like a satellite in orbit, independent of the realities on the ground. The other approach is one that looks at reality, and what people can handle before taking a stand. They are different, but both approaches can lead to revolutionary change in the face of a tradition they think is deficient. Some rabbis will encourage people to change their behavior so it follows the pure halachic root. Others will suggest abandoning a humra that isn’t fitting with the realities on the ground.

- I came across an interesting quote from Chovot HaLevavot. He writes: “One of the components of caution is not being overly cautious” and if one was to be afraid, because of caution, not to say anything new, then no one could have ever said anything from the time of the Prophets. This is a critical aspect for understanding the strength of halacha, and as a wise man once said “with great strength comes great responsibility”.

- One of the wonderful things about halacha as a guide to religious life is its capability to empower a person. And the engine that gives halacha that power is the study of Torah. Everyone can study Torah and everyone can touch the halacha. When I was in yeshiva and asked my Rosh Yeshiva a halachic question, it was his custom to present the various sides to the issue and let the student decide for himself. (From what I’ve read, that was also the custom of his rav, Rav Gustman.) Why is this so important? In principle we shouldn’t need Torah study in order to determine what to do halachically – it’s enough to see what everyone else is doing, or at the most get a simple answer to a question – from a rabbi or a book. However there is something much deeper here. The gemara in Sota 22a states:

The Tannaim (scholars from the mishnah) destroy the world" Could one truly think they destroy the world? Ravina explains that the above source refers to those who make halakhic decisions based on mishnayot. We also learned this in a Beraita: R. Yehoshua said "Are they destroyers of the world? Do they not build the world....? Rather, we are talking about those that decide halakha straight out of mishnayot."

Rashi explains that the reason that by only looking at the mishna, the person will end up making mistakes. But the Maharal in Netivot HaTorah (15) says that the gemara is not referring to a case where the person will err. Rather the gemara is talking about a case where the halacha might technically be correct, but the person avoided studying the Torah sources in order to determine what to do. Since the entire world exists for Torah study, by taking a quick fix – the “tannaim are destroying the world.” The Maharal even goes so far as to say that it is better to err in judgment than to come to a decision by not studying deeply! That is the empowerment that the halacha gives. Mesoret – with all its significance – can’t come close. - One last anecdote: In Abba Eban’s autobiography (which I’m reading now, but that’s for another post), he describes meeting Albert Einstein at a banquet, and noticing that despite wearing “immaculate evening dress” he wasn’t wearing socks. I’ve found a number of quotes on the internet from Einstein about wearing socks, but what he told Eban fits my line of thought perfectly:

“In conversation he explained to me that ... [he] knew perfectly well what he was doing. He was quite simply devoted to rationality. He did not like doing things which had no empirical or logical explanation. There was no scientific way of proving that it was necessary or useful to wear both socks and shoes. One of these acts could be justified by the need to cover the feet; two of them seemed redundant. If I could refute what he had said, he would consider changing his habitual conduct.”

This leads me to thinking about the Nobel Prize given to Prof Aumann of the "Center for Rationality" at Hebrew University, but I think that also will be for another post.

Monday, October 10, 2005

could I convince Tevye to make aliya?

So the halacha vs mesoret issue is still chasing me. I have a few more things I think I'd like to say (although this probably won't be the last word on the topic.)

First of all, after quoting Hayim Soloveitchik's article, I realized I forgot to quote the classic rebuttal: Tevye!

[TEVYE] Tradition, tradition! Tradition! Tradition, tradition! Tradition!Of course the question remains what happened to Tevye...

[TEVYE & PAPAS] Who, day and night, must scramble for a living, Feed a wife and children, say his daily prayers? And who has the right, as master of the house, To have the final word at home? The Papa, the Papa! Tradition. The Papa, the Papa Tradition.

[GOLDE & MAMAS] Who must know the way to make a proper home, A quiet home, a kosher home? Who must raise the family and run the home, So Papa's free to read the holy books? The Mama, the Mama! Tradition! The Mama, the Mama! Tradition!

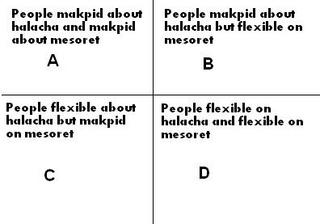

The next issue is perhaps there isn't a simple distinction between anshei mesoret and anshei halacha. Maybe it's a matrix (that's how most of the sugyot in the gemara were presented in my yeshiva):

So maybe I'm B, and my rivals on the community issues are C. But maybe we both need to be striving to reach A or at least reach a balance. Or maybe all the approaches are legitmate.

I'm still not sure.

The last point is an issue I've been meaning to blog about for a while. One of the issues that bothers me the most as a Religious Zionist Baal Teshuva is the fact that there are so many Orthodox Jews who simply ignore what seems to be the clear halachic opinion - that they must make aliya. For a long time I've thought of making a comprehensive web site arguing against every possible excuse to remain in chutz l'aretz. I still hope to do that someday (soon).

But maybe I'm fighting an impossible battle? Or at least ignoring the main point, that those who are committed to mesoret over the halacha won't care that the halacha clearly states they need to make aliya, for they have a tradition from their parents and teachers that it's fine to stay in the States!

I found a letter I wrote to the leadership of Bnei Akiva back in 1997. Looking back at it now, I'm not sure if I was naive or maybe smarter then than I am now. What do you think?

I would like to relate to an issue brought up at the recent meeting of the Moetza Olamit of Bnei Akiva. Much was made there of the recent trend towards "chareidiazation" in the Orthodox communities in the gola, particularly in America. This trend was the basis of a proposal on the one hand to make the tnua entirely separate, and on the other hand to even question whether we should be pushing aliya at all. These suggestions seem to me to be putting the tnua on the defensive, when in fact, we can be using these trends to our advantage.

I believe, in fact, that it is a mistake to refer to the current trends in the gola as "chareidiazation". The truth is that the Modern Orthodox community is not heading in the direction of Charedim as we are familiar with the concept. In the average Modern Orthodox family, both the husband and wife are active members of the community in which they live, and there is a strong emphasis on success in limudei chol. There is also still strong support for Tzionut, in as much as Medinat Yisrael is viewed as a positive entity (even if they disagree with its policies).

What we are seeing in the gola, is rather a trend towards chumrot in halacha, and hakpada in mitzvot. As HaRav Druckman pointed out in the meeting, this is in itself is a positive development. There is much more limud torah, and concern for mitzvot than there was in the past. This trend exists among the Orthodox communities in general, and is encouraged by "Ba'alei Tshuva" movements such as NCSY, Aish HaTorah and Chabad. Part of this trend might also be attributed to the success of the shana b'aretz programs in yeshivot, which Bnei Akiva can even take some credit for.

What Bnei Akiva needs to do in these circumstances, is to "ride on the back" of these trends. We need to strongly point out, both to our chanichim, but perhaps more importantly to their parents, rabbis and community leaders, that a life of hakpada on mitzvot can not ignore the overwhelming significance of the mitzva of living in Eretz Yisrael.

We need to point out that the vast majority of Rishonim and large numbers of Achronim felt that living in Eretz Yisrael was a mitzva. We need to show that if one is trying to live a life of chumrot, one can not ignore a mitzva d'oraita with such a strong basis in chazal.

We are now davka in a particularly ripe time for emphasizing this mitzva. While rates of religious aliya from the West are not what we would like, the spiritual and halachic leadership of Orthodoxy is moving to Israel. With the passing in the past few years of the gedolim of Orthodoxy in America - R' Moshe Feinstein, R' Y.D. Soloveitchik, the Lubavitcher Rebbe z"l - the center of Torah in the world is firmly being placed in Israel.

Again, a lot of this trend can also be attributed to the fact that so many of the members of the Orthodox community have learned in Yeshivot in Israel, and particularly the young rabanim, and view Israeli Roshei Yeshivot as their halachic authority.

How do we go about promoting this mitzva? First of all, we have to be aggressive. We must place the mitzva of aliya on the same level as shmirat shabbat or kashrut. As far as practical plans, I suggest we act on two levels: activity in the gola, and activity within the yeshivot in Aretz. In Chutz L'Aretz, we need to get our idea out in the widest possible fashion. This does not need to be a very expensive project. First of all, I would suggest translating and publicizing currently existing books such as MeAfar Kumi by Tzvi Glatt HY"D and Em HaBanim Smecha by R' Teichtel HY"D. Other books can be translated, or collections of articles and teshuvot can be assembled and published. New articles and books can also be written to explain the significance of the mitzva. These publications can be authorized by the WZO, and be made accessible to the Orthodox public, rabbis and schools. I also believe that to publicize an idea like this, the internet can be a very helpful tool. It is inexpensive, and has a huge audience.

We should also take advantage of the currently existing network of Jewish newspapers and journals. We can write columns, letters to the editor and serve as subjects for news stories reflecting our emphasis on the mitzva of living in Israel. We can also use Bnei Akiva's parshat hashavua sheets to promote these views, as I did when I edited them for Bnei Akiva during my shlichut.

We also must confront Orthodox rabbis, schools, and movements as regards their views on this mitzva. If they believe that an obligation exists to live in Eretz Yisrael, how do they promote it? If they do not believe such an obligation exists, what are their sources?

Questionnaires can be sent to community rabbis, school principals and Roshei Yeshiva and movement heads asking them to clarify their views, with the option of publicizing the results. We should also use existing educational frameworks of our own, such as camps and kollelim, and insist that they encourage aliya from the point of view as a mitzva as well.

As far as the shana b'aretz is concerned, we must take maximum advantage of this very influential period in a young person's life. Many students who come here find themselves more religiously committed at the end of the year, and we must emphasize that this religious commitment must include a commitment to aliya. In principle, this should be easy - the yeshivot are in Israel, so the yeshivot should naturally support aliya. But we see that despite the thousands who learn in yeshivot in Israel, only a small percentage make aliya. Individual yeshivot might be afraid to push aliya as an obligation too strongly, from the fear that parents might be discouraged to send their children to such a yeshiva. But if a concerted effort was made to organize a joint front of all or almost all yeshivot, no individual yeshiva would have to be concerned. And I am not recommending that we encourage aliya immediately after the shana b'aretz, both for the fact that it would discourage parents from sending their children to Israel, and also how it would leave a significant leadership gap in the gola.

With the implementation of these proposals, I believe we can increase the "relevancy" of Bnei Akiva, while remaining true to our principals. We can also increase our influence beyond our own camp to all of Orthodoxy, perhaps influencing the kiruv movements as well.

I hope these suggestions are thought provoking and provide for fruitful discussion. In my opinion, these issues are appropriate for discussion at the upcoming veida, but can be put into place even before it.

Sunday, October 09, 2005

halacha vs mesoret

I've been involved recently in a number of disputes in our shul. I prefer not to get into the details here, but I'll say this: in one issue I wanted to enable an activity that I felt was in the boundaries of halacha, whereas in the other people insisted in doing something I felt was against the normative halacha and the opinion of our local rabbi. In both cases, I more or less lost in my campaign. (And in case anyone reading this is aware of the circumstances, of course I was not the only, or even main, proponent/opponent in either case.)

Someone pointed out the irony that the same people who weren't willing to allow the change that the halacha enables, had no problem going against the rabbi and the halacha about the other issue. I mentioned this to a neighbor I respect, and he pointed out something I hadn't really considered before.

He said there are two types of approaches to Orthodoxy (my words, not his). There are those that look at the halacha and those that look at the mesoret. He claimed that the approach of American rabbis was to look at the books, at the halacha, while the Israeli approach was to look at the mesoret, the tradition.

According to this approach, there wasn't a contradiction in the behavior I mentioned above. In both cases, the parties were interested in what the mesoret was, regardless of the halacha.

When I mentioned that I couldn't help identifying more with the halacha than with (only) the mesoret, he said that made sense. I thought he would say because of my baal teshuva background (I didn't grow up with any signficant traditions to have difficulty breaking with), but he thought it was davka that I went to Yeshivat HaKibbutz HaDati. He claimed that YKD is known for focusing on halacha over mesoret (although I assume he meant more for kula than for chumra.)

That seemed strange to me, since I've always considered YKD to be the farthest thing from a Baal Teshuva yeshiva. When I first went there, and had difficulty keeping up, I considered switching to Machon Meir, which was (maybe still is) the only real Religious Zionist baal teshuva yeshiva. I ended up sticking it out, and I'm certainly glad I did.

But this got me thinking - why is this the case? Why don't most baalei teshuva become anshei halacha instead of anshei mesoret (to invent a dialectic I'm not sure Rav Soloveitchik would agree with)? I think the answer can be found in Haym Soloveitchik's famous article, RUPTURE AND RECONSTRUCTION ( http://www.lookstein.org/links/orthodoxy.htm ). Here he discusses how "mimetic tradition" ends up taking precedence over "the written law." Now he's not only talking about baalei teshuva, but the charedi move to the right in general. He claims that this somewhat recent change came from the break in the chain of tradition with the world of Eastern Europe, by both the encounter with modernity and of course the Shoah. Without a grandfather to follow, the best choice is to take the strictest route. (I highly recommend reading the whole article; my short summary doesn't do it justice.)

When we lived on Kibbutz Yavne, there was an ulpan giyur where potential converts retrieved their pre-conversion training. So I got to know a lot of converts there. I think there's a great similarity between converts and baalei teshuva, especially in their motivation. Many of them are looking for a new family. So they grab on to the traditions, maybe even more than the halacha.

As I've written earlier, I got lucky. I didn't need to do that, I think primarily by attaching myself to rabbis, real talmidei chachamim, instead of other baalei teshuva. So perhaps I'm the exception - a baal teshuva "Ish Halacha".

But still, two things about the approach of the "mesoret" camp bother me. One, I love to argue. I find logic intoxicating, and find few greater pleasures than proving my point. Within the 4 amot of halacha - everything is up for grabs. You bring a source from here - I'll bring a source from there. In the end one side will likely win (unless we're using the Breuer approach to Tanach), but the weapon is logic. Everyone has a fair chance. But how can you argue with mesoret? It doesn't seem fair in general, and as a ba'al teshuva, it puts me at a distinct disadvantage. (Although on a personal level I can get out of many minhagim by saying "I do what my father does..."

And secondly, the anshei mesoret aren't really anshei mesoret. They're rebels as well, although maybe they won't admit to joining Shachal's "HaMered HaKadosh." They don't wear the same clothes or kippas as their great-grandfathers. And probably some of their ancestors objected to Zionism, which was of course a great rebellion. They studied in universities, their daughters and wives study Torah in ways the previous generations never would have, most watch TV and the list goes on and on. So who are they to say that my rebellion against mesoret, especially when it's in the boundaries of halacha, and even motivated by halacha, isn't legitimate?

So how do you have a successful halachic rebellion? That's the $64,000 question. What I've been hearing from friends who know - by education and baby steps. It's hard for a not-so-patient person like me, but I guess there isn't much other choice.

P.S. In the course of a Google search for this post, I came across this article by Rabbi Saul Berman. http://www.edah.org/backend/coldfusion/search/diverse.cfm . Food for thought.

Sunday, October 02, 2005

Seven Species - Seven Holidays

The following is something I thought of a few years ago. I asked around, but no one ever really had anything to add. At least it can be food for thought before this holiday season...

I've noticed a certain connection between each of the seven species of Eretz Yisrael and seven of the major holidays. Some are more obvious, others less so.

- Rosh Hashanah - Pomegranate, as the custom to eat pomegranates on Rosh Hashanah

- Yom Kippur - Fig, since Adam and Chava used fig leaves to cover the nakedness exposed by their first sin

- Sukkot -- Date, the lulav is from the date tree

- Chanukah -- Olive, the olive oil used to light the menorah

- Purim -- Grape, wine plays a major role in both the Megillah and the customs of Purim

- Pesach - Barley, the omer sacrifice brought first on Pesach is barley, "aviv" in Hebrew, and Pesach is in the month of Aviv

- Shavuot - Wheat, the two loaves offering brought on Shavuot is from wheat

Has anyone heard something similar to this?